ABSTRACTChilean species of marine macroalgae with amphitropical distributions oftentimes result from introductions out of the Northern Hemisphere. This possibility was investigated using haplotype data in an amphitropical red macroalgae present in Chile, Callophyllis variegata. Published sequence records from Canada and the United States were supplemented with new collections from Chile (April 2014–November 2015). Specimens of C. variegata were amplified for the 5′ end of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (COI-5P) and the full length nuclear internal transcribed spacer region. Haplotype networks and biogeographic distributions were used to infer whether C. variegata was introduced between hemispheres, and several population parameters were estimated using IMa2 analyses. C. variegata displayed a natural amphitropical distribution, with an isolation time of approximately 938 ka between hemispheres. It is hypothesized that contemporary populations of C. variegata were established from a refugial population during the late Pleistocene, and may have crossed the tropics via rafting on buoyant species of kelp or along deep-water refugia coincident with global cooling, representing a rare case of a non-human mediated amphitropical distribution.

INTRODUCTIONStudies on the phylogeographic history of seaweeds is a burgeoning field (Hu et al. 2016). As genetic data become increasingly available, phycologists are exploring the phylogeographic history of macroalgal species in the context of glaciation events (Maggs et al. 2008, Li et al. 2016), long distance dispersal via rafting on buoyant species of kelp (Fraser et al. 2011, Saunders 2014, Macaya et al. 2016, López et al. 2017) and human-mediated introductions (Thomsen et al. 2016). Such fundamental understanding regarding the origins of local flora serve as critical baseline data during a time of increasing human activities and climate change. Whether a species is considered native or introduced, in particular, has implications for how it is treated in ecological studies and management efforts.

Several temperate species of macroalgae have disjunct populations occurring in both hemispheres (i.e., amphitropical), many of which are the result of introductions out of the North. For instance, most of the 14 macroalgal species reported as being introduced to Chilean waters by Villaseñor-Parada et al. (2018) have distributions in the Northern Hemisphere, 12 of which are considered of northern origin. Another example of a possible introduction into the Southern Hemisphere is Ahnfeltia plicata (Hudson) Fries, which has a broad distribution range extending across both sides of the North Atlantic but has several genetically verified records in Australia and Southernmost Chile (Milstein and Saunders 2012). Mastocarpus is a genus with species distributions previously restricted to the North Pacific before it was recorded in Chilean waters nearly four decades ago, and is thus considered an introduced species to the Southern Hemisphere (Lindstrom et al. 2011, Macaya et al. 2013). Though this non-native species was initially identified as Mastocarpus papillatus (C. Agardh) Kützing (Castilla et al. 2005), Lindstrom et al. (2011) identified this species as Mastocarpus latissimus (Harvey) S. C. Lindstrom, Hughey & Martone based on an internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence from a Chilean specimen, collected at “La Desembocadura” Biobío region. In contrast to the above examples, Asparagopsis armata Harvey has been widely introduced from Australia and New Zealand to northern temperate waters (Ní Chualáin et al. 2004).

Though many amphitropical species are the result of introductions, haplotype data in some species indicate this distribution can occur naturally. Polysiphonia morrowii Harvey, for example, has private haplotypes occurring in the Northwest Pacific, Northeast Atlantic, and Southwest Atlantic, leading Geoffroy et al. (2016) to designate it as a cryptogenic species, though they note multiple introductions could be contributing to the haplotype pattern, a conclusion consistent with earlier reports for this species (Kim et al. 2004). The buoyant brown alga Macrocystis pyrifera (Linnaeus) C. Agardh likely originated in the North Pacific, with dispersal into the Southern Hemisphere sometime within the past 3 millions of years (Ma) (Coyer et al. 2001, Astorga et al. 2012). Laminaria is also hypothesized to have crossed the equator on two separate occasions in the Atlantic, giving rise to Laminaria abyssalis A. B. Joly & E. C. Oliveira and Laminaria pallida Greville (Rothman et al. 2017). Callophyllis variegata (Bory) Kützing also exhibits a disjunct distribution spanning both hemispheres in the East Pacific, but its population history remains unresolved. Callophyllis is considered a speciose genus spanning both hemispheres, however, considerable taxonomic confusion persists in this group (Saunders et al. 2017). The type locality for C. variegata occurs in Chile (Arakaki et al. 2011), yet this species groups with a well-supported cluster of Callophyllis sensu stricto species occurring in the Northeast Pacific (Saunders et al. 2017), suggesting it speciated in the North Pacific and subsequently moved south. Though this species was first described in the South Pacific, the disjunct distribution and its phylogenetic relationship with North Pacific species open the possibility that C. variegata may be non-native to Chile.

This study sought to investigate haplotype patterns in amphitropical populations of the red algae C. variegata. This species is among the economically important seaweeds of Chile, which are harvested for carrageenan and human consumption (Buschmann et al. 2001, Castilla and Neill 2010, Mansilla et al. 2012). Utilizing population level data, the objectives of this study were to (1) determine if C. variegata was introduced between hemispheres; and (2) if C. variegata has been introduced, determine what hemisphere it was introduced out of, or, alternatively, if C. variegata has a naturally occurring amphitropical distribution, what is the nature of its population history (e.g., isolation time, effective populations sizes, migration rates).

MATERIALS AND METHODSIn order to study the phylogeographic distribution of C. variegata, records were amalgamated from several collection episodes spanning 1998–2010, and supplemented with sampling of Chilean specimens (i.e., new samples to this study; April 2014–November 2015) (Supplementary Table S1). During collection, specimens were preserved in silica gel and brought back to the University of New Brunswick for DNA extraction (Saunders and McDevit 2012) and amplification of the 5′ end of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (COI-5P) using M13LF3 and M13Rx forward and reverse primers (Saunders and Moore 2013). The full length nuclear ITS was amplified using P1 and G4 forward and reverse primers (Saunders and Moore 2013). Polymerase chain reaction products were sent to Genome Quebec for forward and reverse sequencing using the sequencing primers M13F and M13R for COI-5P, and P1 and G4 for ITS. All genetic data were edited in Geneious ver. 10.2.3 (Kearse et al. 2012). The lengths of the sequenced amplicons were 664 and 683 base pairs for COI-5P and ITS, respectively. See Supplementary Table S1 for GenBank accession numbers. Insertions and/or deletions were removed from these networks, as were heterozygous individuals (Supplementary Table S1).

IMa2 analyses were used to test various population scenarios in C. variegata and to estimate the timing of divergence between North and South populations. A two-population model (North and South) with migration was tested using a previously calibrated COI-5P clock of 0.007 substitutions site−1 Ma−1 (Bringloe and Saunders 2018). The mutation rate for ITS was scaled during IMa2 analyses (IMa2 flag: -y1.1826256). Sequences with ambiguities (i.e., sharing signatures of multiple populations, as in, putatively recombinant haplotypes) were removed from the IMa2 analyses. Once run parameters (priors, heating terms) were optimized, five independent two million length chains were run using an HKY substitution model, and geometric heating (hn = 10), with sampling every 100 steps, for a total of 20,000 geneologies saved run−1. The results from the five runs were combined using L mode, sampling 20,000 saved genealogies, and log-likelihood ratios were used to determine if the full model tested could be rejected in favour of a given nested model (Supplementary Table S2). Values for isolation time and historical effective population sizes are presented in demographic units; the values for effective population size assume a generation time of 1 year.

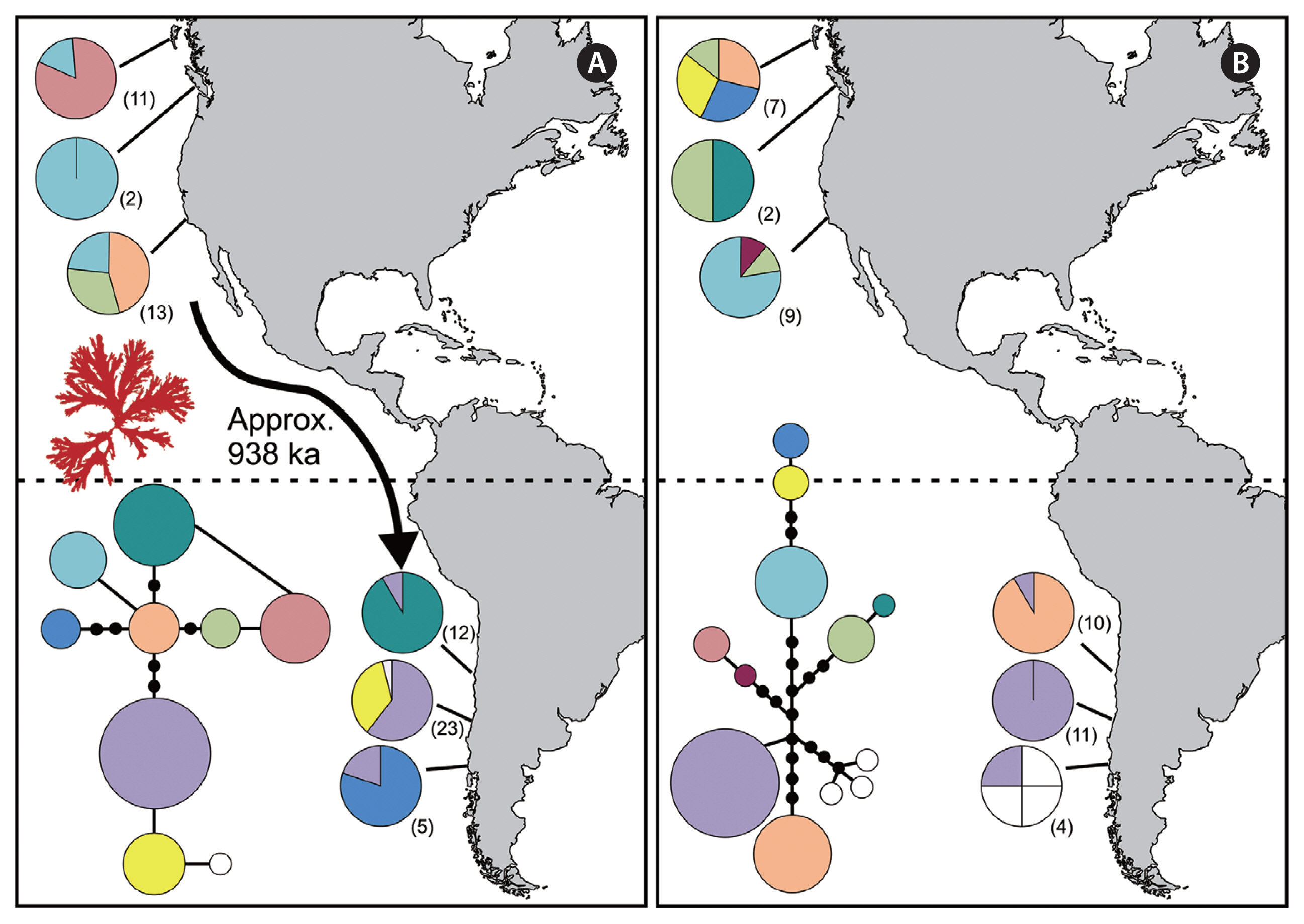

RESULTSIn total, COI-5P data were obtained for 28 North Pacific and 40 South Pacific specimens of Callophyllis variegata, while ITS data were also obtained for 23 and 32 North and South Pacific specimens, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). Within the ITS data, 6 specimens shared genetic signatures with multiple populations (i.e., additivity at a given site), though none shared signatures between the two hemispheres (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, no haplotypes were shared between North and South hemispheres for C. variegata in both the COI-5P and ITS data. North and South populations were reciprocally monophyletic for the ITS data, but this was not the case for COI-5P (Fig. 1). IMa2 analyses converged on similar values for historical effective population sizes for C. variegata in the North and South Pacific, while the posterior probability for the ancestral population size was largely flat, showing a modest peak at smaller values (Table 1, Fig. 2). Posterior probabilities on migration between North and South populations peaked at 0 (Table 1, Fig. 2). The posterior probability for isolation time between North and South populations peaked at 938 ka, with a flat posterior at higher values (Table 1, Fig. 2).

DISCUSSIONAmphitropical species in the Southeast Pacific, particularly along the Chilean coastline, are typically reported as potential introductions from the Northern Hemisphere (Castilla et al. 2005). Callophyllis variegata occurs in the North and South Pacific, but its phylogeographic history remained unresolved. Here, it was determined that C. variegata exhibits a naturally occurring distribution between hemispheres, as in, its distribution does not appear to have been mediated by recent human activity. This was first evidenced by the lack of shared haplotypes between North and South populations (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the COI-5P data exhibited signs of incomplete lineage sorting, in contrast to the ITS results (Fig. 1). The northern and center portions of the Chilean coastline are characterized by patchy populations and strong genetic drift in algal populations, facilitated in part by recurrent bottlenecks due to El Niño events and tectonic activity (Guillemin et al. 2016). These factors, combined with the constrained effective population size of the mitochondrial genome, likely result in mutations becoming rapidly fixed in Chilean sub-populations. If the ancestral Chilean COI-5P haplotype has since diverged in several directions with little gene flow between populations, this in turn would hamper the sorting of Southern lineages from Northern populations. The ITS data, in contrast, demonstrated that Southern lineages have sorted completely from Northern counterparts (Fig. 1B), further corroborating our conclusion that C. variegata has a natural amphitropical distribution.

North and South populations of C. variegata likely stemmed from a refugial northern population during the Pleistocene. In particular, C. variegata is phylogenetically embedded in a well-supported clade of North Pacific species (Saunders et al. 2017), suggesting the species originated in the Northern hemisphere. Given the alternative scenario (speciating in the Southern Hemisphere) requires C. variegata to have migrated across the tropics twice, it can be speculated that speciation in the Northern Hemisphere is the most plausible history. Further supporting this hypothesis, the putative ancestral haplotype according to coalescent theory should be the central haplotype in the COI-5P network (depicted as orange) (Fig. 1A), which occurs in the Northern Hemisphere (Castelloe and Templeton 1994); the ancestral haplotype in ITS presumably has been lost or has yet to be sampled (Fig. 1B). The lack of detectable historical migration between hemispheres also suggests gene flow between North and South populations is exceedingly rare (Table 1, Fig. 2). Also noteworthy is that the historical effective population sizes of North and South populations were nearly the same (Table 1, Fig. 2), closely approaching significance in terms of being favorable compared to the full (free to vary) IMa2 model (p = 0.945) (Supplementary Table S2). This complicates interpretation of the location of origin for C. variegata; had one historical effective population size been significantly greater than the other, a longer population history could be inferred from a given hemisphere. The similar historical effective populations sizes of North and South populations of C. variegata further suggests these populations were established from the same source at approximately the same time. It is possible these populations originated from a refugium that occurred south of Northern Hemisphere ice sheets during the Pleistocene, through considerably more sampling would be needed to establish a refugial location (see Dyke and Prest 1987 for Northern Hemisphere ice sheets during the Last Glacial Maximum). Indeed, IMa2 analyses estimated the isolation time between North and South populations to be approximately 938 ka, a time during which glaciation events were shifting towards 100 ka cycles (note the minimum Highest Posterior Density estimate of 404 ka and an unresolved maximum value) (Table 1, Fig. 2) (Lisiecki and Raymo 2005, Miller et al. 2010).

If contemporary populations of C. variegata were established in both hemispheres from a glacial refugial source, this may explain how the species was able to cross into the Southern hemisphere. Glaciation will have constricted temperate regimes towards the equator, pushing the ancestral population of C. variegata into southerly waters and likely creating a genetic bottleneck (Bennett and Provan 2008). Movement across the tropical barrier into the Southern Hemisphere may have been facilitated by buoyant species of kelp, which are known to raft other species of algae and invertebrates across large oceanic distances (Fraser et al. 2011, Saunders 2014, Macaya et al. 2016). Rafting of C. variegata along the Chilean coastline may have also occurred (López et al. 2017), though sampling from more sites is needed to confirm this hypothesis. M. pyrifera is a candidate for having transported C. variegata across the equator, as populations in the Southern Hemisphere are thought to have been established from Northern populations during the Pleistocene (Coyer et al. 2001, Astorga et al. 2012). Indeed, several species of Callophyllis have been linked with transport on buoyant species of macroalgae, including C. variegata (Macaya et al. 2016). In an experimental study, Edgar (1987) recorded Callophyllis rangiferina (R. Brown ex Turner) Womersley growing on M. pyrifera after more than half a year at sea, which suggests C. variegata could have survived the long journey across the equator. Alternatively, if C. variegata persisted in deep water refugia (Graham et al. 2007), it may have crossed without the aid of rafting kelp by using these refugia as stepping stones. Though this hypothesis is rather speculative, recent work has revealed red bladed species of macroalgae growing in deep water tropical habitats; for instance, Cryptonemia abyssalis C. W. Schneider & Popolizio is a recently described species collected from a depth of 90 m off the coast of Bermuda (Schneider et al. 2018). The patterns observed here seem tenable to the first hypothesis (i.e., no contemporary connectivity between North and South populations) (Table 1, Fig. 2).

ConclusionIntroductions of marine algal species are a concern worldwide. Though the Southeast Pacific coastline is relatively “pristine” compared to other areas (Thomsen et al. 2016), it has not been exempt from human-mediated introductions of species (Castilla et al. 2005, Castilla and Neill 2010). The results presented here have demonstrated that the amphitropical C. variegata has a natural distribution across both hemispheres, and that contemporary North and South populations were likely established during the late Pleistocene, possibly via rafting on M. pyrifera (Coyer et al. 2001). Regardless of how C. variegata managed to cross the tropical barrier during the Pleistocene, it serves as a rare example of a species of algae with a non-human mediated amphitropical distribution.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALSupplementary Table S1. Specimen list and collection information for Callophyllis variegata (https://www.e-algae.org).

Supplementary Table S2. Log-likelihood ratio tests for simplified IMa2 models (https://www.e-algae.org).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSWe thank the various people involved with the collection of specimens over the years. In particular, we thank Cody Brooks, Janelle Doucet, and Tanya E. Moore for helping to generate sequence data. This project was funded by a Discovery Grant to G. W. Saunders (170151-2013) and Centro Fondap-IDEAL (15150003) funded by Conicyt to E. C. Macaya. This project was also supported by the Natural Sciences & Engineering Research Council of Canada through an NSERC Post-Graduate Scholarship to T. T. Bringloe and the New Brunswick Innovation Foundation.

Fig. 1

Callophyllis variegata haplotype networks and biogeographic distributions in the Pacific Ocean for mitochondrial COI-5P (A) and nuclear internal transcribed spacer (ITS) (B) genes. The dashed line represents the equator. Numbers in parentheses refer to sample sizes from given sites. Black circles indicate hypothesized substitutions between clades. The size of the circles is proportional to sampling frequency. In the COI-5P map, the arrow refers to the putative migration event that established populations in the Southern Hemisphere, including the estimated isolation time estimate (ka).

Fig. 2Posterior probabilities for effective population sizes (A), migration rates (B), and isolation time (years) (C) based on 100,000 sampled COI-5P and internal transcribed spacer genealogies in Callophyllis variegata.

Table 1Values for population parameters for amphitropical Callophyllis variegata, estimated using IMa2 REFERENCESArakaki, N., Alveal, K., Ramírez, ME. & Fredericq, S. 2011. The genus Callophyllis (Kallymeniaceae, Rhodophyta) from the central-south Chilean coast (33° to 41° S), with the description of two new species. Rev Chil Hist Nat. 84:481–499.

Astorga, MP., Hernández, CE., Valenzuela, CP., Avaria-Llautureo, J. & Westermeier, R. 2012. Origin, diversification, and historical biogeography of the giant kelps genus Macrocystis: evidences from Bayesian phylogenetic analysis. Rev Biol Mar Oceanogr. 47:573–579.

Bringloe, TT. & Saunders, GW. 2018. Mitochondrial DNA sequence data reveal the origins of postglacial marine macroalgal flora in the Northwest Atlantic. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 589:45–58.

Buschmann, AH., Correa, JA., Westermeier, R., Hernández-González, MC. & Norambuena, R. 2001. Red algal farming in Chile: a review. Aquaculture. 194:203–220.

Castelloe, J. & Templeton, AR. 1994. Root probabilities for intraspecific gene trees under neutral coalescent theory. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 3:102–113.

Castilla, JC. & Neill, PE. 2010. Marine bioinvasions in the Southeastern Pacific: status, ecology, economic impacts, conservation and management. In : Rilov G, Crooks JA, editors Biological Invasions in Marine Ecosystems: Ecological, Management, and Geographic Perspectives. Springer, Berlin, 439–458.

Castilla, JC., Uribe, M., Bahamonde, N., Clarke, M., Desqueyroux-Faúndez, R., Kong, I., Moyano, H., Rozbaczylo, N., Santelices, B., Valdovinos, C. & Zavala, P. 2005. Down under the Southeastern Pacific: marine non-indigenous species in Chile. Biol Invasions. 7:213–232.

Coyer, JA., Smith, GJ. & Andersen, RA. 2001. Evolution of Macrocystis spp. (Phaeophyceae) as determined by ITS1 and ITS2 sequences. J Phycol. 37:574–585.

Dyke, A. & Prest, V. 1987. Paleogeography of northern North America,18, 000–5,,000 years ago. Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, 1–3.

Edgar, GJ. 1987. Dispersal of faunal and floral propagules associated with drifting Macrocystis pyrifera plants. Mar Biol. 95:599–610.

Fraser, CI., Nikula, R. & Waters, JM. 2011. Oceanic rafting by a coastal community. Proc R Soc B. 278:649–655.

Geoffroy, A., Destombe, C., Kim, B., Mauger, S., Raffo, MP., Kim, MS. & Le Gall, L. 2016. Patterns of genetic diversity of the cryptogenic red alga Polysiphonia morrowii (Ceramiales, Rhodophyta) suggest multiple origins of the Atlantic populations. Ecol Evol. 6:5635–5647.

Graham, MH., Kinlan, BP., Druehl, LD., Garske, LE. & Banks, S. 2007. Deep-water kelp refugia as potential hotspots of tropical marine diversity and productivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 104:16576–16580.

Guillemin, ML., Valero, M., Tellier, F., Macaya, EC., Destombe, C. & Faugeron, S. 2016. Phylogeography of seaweeds in the South East Pacific: complex evolutionary processes along a latitudinal gradient. In : Hu Z-M, Fraser C, editors Seaweed Phylogeography: Adaptation and Evolution of Seaweeds under Environment Changes. Springer, Dordrecht, 251–277.

Hu, ZM., Duan, DL. & Lopez-Bautista, J. 2016. Seaweed phylogeography from 1994–2014 an overview. In : Hu Z-M, Fraser C, editors Seaweed Phylogeography: Adaptation and Evolution of Seaweeds under Environmental Change. Springer, Dordrecht, 3–22.

Kearse, M., Moir, R., Wilson, A., Stones-Havas, S., Cheung, M., Sturrock, S., Buxton, S., Cooper, A., Markowitz, S., Duran, C., Thierer, T., Ashton, B., Meintjes, P. & Drummond, A. 2012. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 28:1647–1649.

Kim, M., Yang, EC., Mansilla, A. & Boo, SM. 2004. Recent introduction of Polysiphonia marrowii (Ceramiales, Rhodophyta) to Punta Arenas, Chile. Bot Mar. 47:389–394.

Li, JJ., Hu, ZM. & Duan, DL. 2016. Survival in glacial refugia versus postglacial dispersal in the North Atlantic: the cases of red seaweeds. In : Hu Z-M, Fraser C, editors Seaweed Phylogeography: Adaptation and Evolution of Seaweeds Under Environmental Change. Springer, Dordrecht, 309–330.

Lindstrom, SC., Hughey, JR. & Martone, PT. 2011. New, resurrected and redefined species of Mastocarpus (Phyllophoraceae, Rhodophyta) from the Northeast Pacific. Phycologia. 50:661–683.

Lisiecki, LE. & Raymo, ME. 2005. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic 18O records. Paleoceanography. 20:PA1003 pp.

López, BA., Tellier, F., Retamal-Alarcón, JC., Pérez-Araneda, K., Fierro, AO., Macaya, EC., Tala, F. & Thiel, M. 2017. Phylogeography of two intertidal seaweeds, Gelidium lingulatum and G. rex (Rhodophyta: Gelidiales), along the South East Pacific: patterns explained by rafting dispersal? Mar Biol. 164:188 pp.

Macaya, EC., López, B., Tala, F., Tellier, F. & Thiel, M. 2016. Float and raft: role of buoyant seaweeds in the phylogeography and genetic structure of non-buoyant associated flora. In : Hu Z-M, Fraser C, editors Seaweed Phylogeography: Adaptation and Evolution of Seaweeds Under Environmental Change. Springer, Dordrecht, 97–130.

Macaya, EC., Pacheco, S., Cáceres, A. & Musleh, S. 2013. Range extension of the non-indigenous alga Mastocarpus sp. along the Southeastern Pacific coast. Rev Biol Mar Oceanogr. 48:661–665.

Maggs, CA., Castilho, R., Foltz, D., Henzler, C., Jolly, MT., Kelly, J., Olsen, J., Perez, KE., Stam, W., Väinölä, R., Viard, F. & Wares, J. 2008. Evaluating signatures of glacial refugia for North Atlantic benthic marine taxa. Ecology. 89(11 Suppl):S108–S122.

Mansilla, A., Ávila, M. & Yokoya, NS. 2012. Current knowledge on biotechnological interesting seaweeds from the Magellan Region, Chile. Braz J Pharmacogn. 22:760–767.

Miller, GH., Brigham-Grette, J., Alley, RB., Anderson, L., Bauch, HA., Douglas, MSV., Edwards, ME., Elias, SA., Finney, BP., Fitzpatrick, JJ., Funder, SV., Herbert, TD., Hinzman, LD., Kaufman, DS., MacDonald, GM., Polyak, L., Robock, A., Serreze, MC., Smol, JP., Spielhagen, R., White, JWC., Wolfe, AP. & Wolff, EW. 2010. Temperature and precipitation history of the Arctic. Quat Sci Rev. 29:1679–1715.

Milstein, D. & Saunders, GW. 2012. DNA barcoding of Canadian Ahnfeltiales (Rhodophyta) reveals a new species: Ahnfeltia borealis sp. nov. Phycologia. 51:247–259.

Ní Chualáin, F., Maggs, CA., Saunders, GW. & Guiry, MD. 2004. The invasive genus Asparagopsis (Bonnemaisoniaceae, Rhodophyta): molecular systematics, morphology, and ecophysiology of Falkenbergia isolates. J Phycol. 40:1112–1126.

Rothman, MD., Mattio, L., Anderson, RJ. & Bolton, JJ. 2017. A phylogeographic investigation of the kelp genus Laminaria (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae), with emphasis on the South Atlantic Ocean. J Phycol. 53:778–789.

Saunders, GW. 2014. Long distance kelp rafting impacts seaweed biogeography in the Northeast Pacific: the kelp conveyor hypothesis. J Phycol. 50:968–974.

Saunders, GW., Huisman, JM., Vergés, A., Kraft, GT. & Le Gall, L. 2017. Phylogenetic analyses support recognition of ten new genera, ten new species and 16 new combinations in the family Kallymeniaceae (Gigartinales, Rhodophyta). Cryptogam Algol. 38:79–132.

Saunders, GW. & McDevit, DC. 2012. Methods for DNA barcoding photosynthetic protists emphasizing the macroalgae and diatoms. Methods Mol Biol. 858:207–222.

Saunders, GW. & Moore, TE. 2013. Refinements for the amplification and sequencing of red algal DNA barcode and RedToL phylogenetic markers: a summary of current primers, profiles and strategies. Algae. 28:31–43.

Schneider, CW., Lane, CE. & Saunders, GW. 2018. A revision of the genus Cryptonemia (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta) in Bermuda, western Atlantic Ocean, including five new species and C. bermudensis (Collins & M. Howe) comb. Nov Eur J Phycol. 53:350–368.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||